Kazan Federal University scientists discover how to optimize geological exploration work by studying the strontium isotope content in conodonts

Scientists from the Institute of Geology and Petroleum Technologies (IGPT) have refined the strontium curve for the Devonian marine layers of the Volga-Ural oil and gas basin by investigating the strontium isotope content in conodonts—the tooth-like remains of small, free-swimming marine predators.

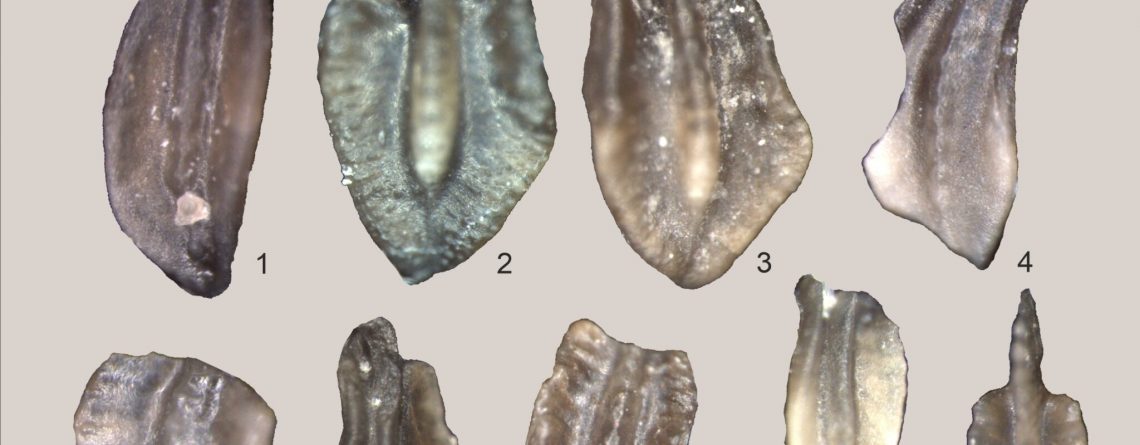

The conodont elements, consisting of minerals from the apatite group, were selected from the extensive collection of the Shtukenberg Geological Museum at Kazan University. In the 1960s and 1980s, this collection was used to create a detailed stratigraphic scheme of the Devonian period for the Volga-Ural oil and gas province.

The new scientific data are presented in a paper published in the journal Georesursy (Georesources).

“Many are convinced that scientists figured out Earth’s history long ago: there is a lot of information, and artificial intelligence can ‘explain’ any topic. However, knowledge is born not from beautiful words, but from measurements that can be verified,” says Vladimir Silantyev, Acting Director of IGPT and Chair of the Department of Paleontology and Stratigraphy. “New methods allow us to establish what the planet’s past was like, literally at the atomic level, through the isotopes of chemical elements. We used strontium as a natural time marker and, based on its isotopic composition, refined the geochemical conditions of the formation of the Devonian marine layers in the Volga-Ural region – source rocks, reservoirs, and cap rocks.”

The professor explains why millimeter-sized conodonts were chosen for the experiments.

“In most cases, the material that makes up our planet is unsuitable for detailed measurements of ancient isotopic ratios because it is usually altered and reworked by bacteria, recrystallization, and weathering. Conodonts became a sort of a ‘tin can,’ preserving ancient strontium isotopes to this day,” reports Dr Silantyev.

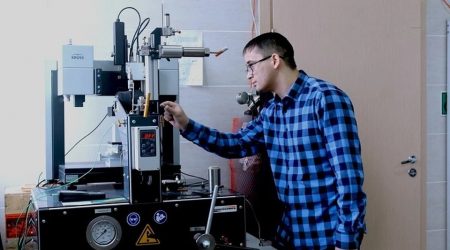

Using Thermal Ionization Mass Spectrometry (TIMS), 19 samples from different stratigraphic levels were analyzed for their 87Sr and 86Sr isotope content. After studying the obtained data, the scientists concluded that it demonstrates good consistency with the global strontium curve (the curve of the 87Sr/86Sr isotope composition) – a graph that reflects variations in strontium isotope composition over time in the oceans. This indicates a stable connection between the studied region and the World Ocean throughout the Middle and Late Devonian.

Danis Nurgaliev, Vice-Rector for Earth Sciences, Corresponding Member of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Tatarstan, and Scientific Director of IGPT, notes that the data will contribute to reducing uncertainty in the exploration and assessment of mineral resources.

“There is nothing more practical than a good fundamental result – this is exactly what can be said about the discovery of the identity between the strontium isotope curve for the Devonian of the Romashkino field and global data. This opens up the possibility of the indisputable application of all patterns of sediment formation in open seas, where ocean level fluctuations controlled all these processes. We assumed this based on previously obtained biostratigraphy data built on conodonts, but in many cases, we lacked ironclad arguments, and the models were very hypothetical. The obtained result completely removed all doubts. We are already revising lithofacies models in oil and gas reservoirs, taking the new data into account to improve the efficiency of the development of the unique Romashkino oil field, the largest in the Volga-Ural province and one of the largest in Russia,” says Dr Nurgaliev.

As is known, the lithofacies characteristics of reservoir rocks allow for the reconstruction of the depositional environment, the determination of the distribution zones of these rocks, and the identification of the most promising areas for oil production.

The research was carried out by KFU scientists within the framework of the Priority 2030 program, using developments obtained during the implementation of projects for the World-Class Research Center for the Rational Development of the Planet’s Liquid Hydrocarbon Reserves (Center for Liquid Hydrocarbons) and applied work for PJSC Tatneft.